Despite the many fascinating nuances of documentable history, would-be researchers still need to be extremely wary of skewing their research, consciously or unconsciously, to fit a conclusion they wish to be true. And when it comes to topics which are near and dear to one’s interests—or worse yet, one’s family—this can be very difficult indeed. Yet the serious historian must strive to be objective in their research, regardless of their personal connection to any topic.

Such is the case with the story of one “Lolly” (or Lowly) “Todd” Childs—or whatever her maiden name really was. The nation’s century-and-a-half obsession with Lincolniana makes the temptation to believe a series of tertiary source newspaper articles from the early 20th century almost overpowering. Those articles—seemingly instigated by her 60- to 70-something-year-old granddaughter, Ann Jane (“Jennie”) Elshiemer—claim that “Lolly” was, in fact, the aunt of Mary Todd Lincoln, wife of 16th president, Abraham Lincoln.

Cherished pieces of folklore and family history are very delicate things indeed, and historians take them on at their peril. The fact is that people want to believe the things which have been passed down over and over, and often take very personally any attempt to debunk them. Historians often get a very negative reputation while simply trying to ferret out myth from verifiable fact. To be true to their profession, however, it is important for historians to not be swayed by the “slings and arrows” of folklore’s caretakers, nor by the tendency to “want” something to be true, but rather to attempt, as much as possible, to base their conclusions on reliable—and verifiable—evidence.

One of the most frustrating aspects of the historical craft for professional historians is the fact that it is often very difficult to prove that something is incontrovertibly true or false. That being said, in spite of this difficulty, it is often possible to make one’s point through, shall we say, the “back door.” In other words, instead of proving something is absolutely true or false, one sets about proving that it is either very likely false, or that the opposite is very likely true. It has been said that “if it looks like a duck, swims like a duck and quacks like a duck, it is probably a duck.” By extension, then, the opposite should be true: if it does NOT look, swim, nor quack like a duck, chances are it IS NOT a duck. Sadly, I believe such to be the case with “Lolly” Childs.

The Claim

Perhaps the best place to begin a discussion of Mrs. Childs is with the claim itself. The claim is that “Lolly” (Todd?) Childs (1776-1854), wife of one Stephen Childs and grandmother to Ann Jane (“Jennie”) Ortt Elsheimer, was an aunt to Mary Ann Todd Lincoln. For this to be true, this would logically make her a sister to Robert Smith Todd, Mary’s father. It would also make her (presumably) the child, like Robert Smith, of Levi Todd and Jane Briggs.

Now let’s look at the evidence supporting that claim. With all due respect to those who hold this claim dear, from a professional historian’s point of view, the evidence is virtually transparent. In essence there are but two sets of “documentation” for this claim:

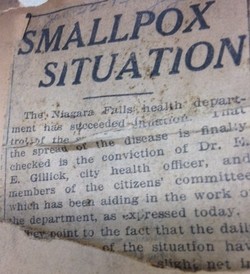

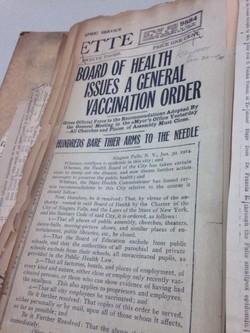

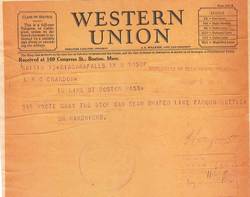

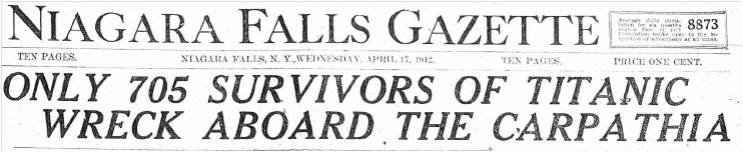

1)-A series of three (3) brief newspaper articles, which appeared in the Niagara Gazette on April 7, 1924, July 28, 1926 and February 12, 1935, respectively. All of these make casual mention of one Jennie Elsheimer being the descendant of a Lolly Todd Childs, who was, in turn, purported to be an aunt of Mary Todd Lincoln. The dates, I think, are not coincidental. The first article appeared on the occasion of the Presbyterian Church completing their centennial celebration. Included in this celebration, not surprisingly, was a retrospective profile of notable members over the years, including one Mrs. Stephen Childs. The second article appeared only two days following the death of Robert Todd Lincoln, son of Abraham and Mary Todd Lincoln. And the third appeared on Abraham Lincoln’s birthday, 70 years following his assassination. It is not surprising that such occasions would result in the “digging up” of bits of folklore, particularly stories that tied local residents—accurately or not—to the great and famous. As noted above, each of these articles took pains to mention that one Jennie Elsheimer, of 1018 South Avenue in Niagara Falls, NY, was a descendant of Mrs. Stephen Childs, and thus a relative of Mary Todd Lincoln.

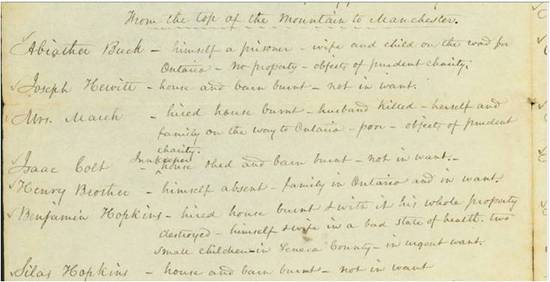

2)-As our second piece of documentation we have a handwritten “family tree” from the Elsheimer family, brought to Oakwood Cemetery by a family member in 2013, in response to a call for information regarding the claim. The chart traces “Jennie” Elsheimer to a Steven [sic] and Lola [sic] Childs. “Lola,” in turn, is listed as the daughter simply of “Mr. Todd” and “Mrs. Todd.” A line suggests a sibling of “Mr. Robert Todd” who is shown as the father of Mary Todd Lincoln. There is no further documentation accompanying this family tree whatsoever. This includes any specific details about the individuals listed on it, such as place of birth (though birth and death years are often shown elsewhere on the tree, though not in every case).

These two sets of “evidence” (the 3 newspaper stories and the handwritten genealogy), along with a few likewise undocumented oral accounts of similar family histories, conclude the materials bolstering the argument that “Lolly” Childs was the aunt of Mary Todd Lincoln. Taken together, there is not a shred of primary documentation shown in these documents, or accompanying them, to verify any of the statements or relationships, relative to Mrs. Childs and Mrs. Lincoln.

Despite the lack of any verifiable documentation to support this purported relationship, as mentioned above it may be possible to prove that one conclusion or another is “plausible,” by examining what verifiable information does exist regarding these two women. So let’s take a look at what we “know” to be true and see where it leads:

What we KNOW to be true, part I- The Childs Family

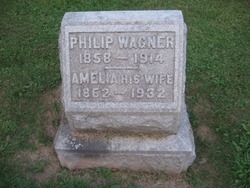

-One “Lolly” (actually listed as “Loly”) Childs was buried in lot 231 at Oakwood Cemetery, NF,

NY on November 26, 1854.[1]

-The same “Lolly” Childs is the grandmother of one Ann Jane (“Jennie”) Ortt Elsheimer. So far,

so good…..

Following these truths with a backward lineage, we find the following:

-Ann Jane Ortt Elsheimer (1860-1950) was the 8th child of David Phillip Ortt (1823-1903) and

Mary Ann Tufford (1818-1906)

-Mary Ann Tufford (1818-1906) was the second child of Phillip Tufford (1795-1870) and

Harriet Childs.

-Harriet Childs (1798-1879) was the eldest child of Stephen Childs (1769-?) and “Lolly” (some

say Sally, which would make sense with Lolly/Loly as a nickname) ______(Todd?!?)

(1776-1854)[2]

This genealogical information also coincides with what is known, independently, about “Lolly,” ie. that she was the wife of one Stephen Childs. It should be noted, however, that nowhere in any of the above documentation does the maiden name of Todd exist in reference to Lolly. It is only in the abovementioned newspaper and genealogical accounts that this name appears.

Following, then, the genealogy and travels of Stephen Childs, Lolly’s husband, we find the following:

-Stephen was born in or about 1769 in Woodstock, Windham County, Connecticut[3]

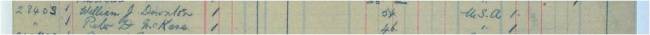

According to official U.S. Census records, we know the following:

-By 1800 he had moved to Fairfield, Franklin County, VT, but probably by 1798 or

earlier.

-In 1810 he is listed at Stephen “Child” (no “s”) in Montgomery County, NY

-In 1820, he is listed again as “Childs” in Lewiston, Niagara County, NY

-In 1830, he is listed as “Child” again, this time in Niagara, Niagara County, NY

-In 1840, it would seem that he is found in China, Genesee County, NY, as the numbers

match. Something could be mislabeled here…..

-In 1850, he is back in Niagara, Niagara County, NY, at age 84, with a wife “Lolly.”

-In 1860, he is listed in Macoupin County, Illinois at the age of 93, but with no wife.[4]

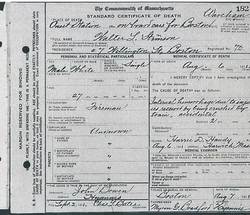

Following the sparse path of “Lolly” Childs, then, we get the following clues:

-According to the 1850 U.S. Census listing for Stephen Childs, she was born around 1776 in

Connecticut

-This compares favorably with other indirect evidence:

-In the 1860 census she fails to appear—this makes sense since she died in 1854,

according to the burial records at Oakwood.

-“Lolly” is listed as being 74 years old in the 1850 census; 1850-74= 1776

-the abovementioned 1840 census listing for China, NY has one female

age 60-69 (“Lolly’s” likely age= 64)

-the abovementioned 1830 census listing for Niagara Cty. has one female

listed age 50-59 (“Lolly’s” likely age= 54)

- the abovementioned 1820 census listing for Lewiston has one female

listed age 26-44. (“Lolly’s” likely age= 44)

- the abovementioned 1810 census listing for Mont. Cty., NY has one

female listed age 26-44 (“Lolly’s” likely age= 34)

- the abovementioned 1800 census listing for Fairfield, VT has one female

listed age 16-25. (“Lolly’s” likely age= 24)[5]

Due to the nature of the census information gathered during those years, “Lolly” is unfortunately not listed by name in any of the census records from 1800-1840. However, having her name and age listed in the entry for Stephen Childs in 1850, and following the statistical data for the prior census listings, presents a highly plausible argument for “Lolly’s” nameless presence in these records.

Conclusions for Part I

Thus, based on the above direct and indirect documentation, the following conclusions may be made:

1)-One Stephen Childs, born about 1769 in Woodstock, CT, married one “Lolly” (maiden

name unconfirmed) prior to the year 1798, when their first child (Harriet) was

born. The marriage location is unknown, but was likely Fairfield, VT. All

secondary references to this marriage, show his wife as “Sally (maiden name

unknown).”

2)-This same Stephen Childs, and his wife, “Lolly” were living in Franklin

County, Vermont in 1798 when Harriet was born.

3)-The movement of the family of Stephen Childs is well-documented through the U.S.

Census returns as having passed from Connecticut to Vermont to New York.

4) While no independent verification of the place of “Lolly’s” birth has been found,

evidence provided by the census documents regarding Stephen Childs supports

the claim of Connecticut as her birth state and approximately 1776 as her birth

year. With no evidence to the contrary, it is reasonably safe to take these two

statements as true.

5) Comparing the information on “Lolly” with that known of Mary Todd Lincoln, in the

year of Mrs. Lincoln’s birth (1818) “Lolly” would have been about 42 years old

and living in either Montgomery or Niagara County, New York. “Lolly’s” age is

thus plausible for an aunt of Mary Todd Lincoln. This alone, perhaps, makes it

worth the trouble to take the next step in our evaluation, an examination of the family history of Mary Todd Lincoln.

What we KNOW to be true, part II: The Case of Mary Todd Lincoln

Having established, with some degree of certainty, a paper trail for Stephen Childs and his wife, let’s take a look at the other side of things: the paper trail for Mary Ann Todd, better known as Mrs. Abraham Lincoln. For better or worse, the Todd family from whence Mary Lincoln hailed is considered by most to be one of the First Families of Kentucky, and thus one of the best-documented families in early America. This makes the task of determining who was where when (and related to whom) a fairly easy task.

The following ancestry of Mary Ann Todd is well known….and well-documented:

-She was born in 1818 to Robert Smith Todd (1791-1849) and Elizabeth (Eliza) Ann

Parker (1794-1825)

-Robert Smith Todd, in turn, was the son of Levi David Todd (1756-1807) and Jane

Briggs (1761-1800), who were married on 25 February, 1779 and had 11 children

including, of course, Robert Smith. When Jane died in 1800, Levi married Jane

Holmes-Tatum (widowed) about 1802, and had one son, James, with this second

wife.[6]

-The typically listed children of Levi Todd are as follows (with their birth dates):

Hannah B. (1781)

Elizabeth (1782)

David (1786)

John (1787)

Nancy (c. 1788…or 1785??)

Ann Maria (1778?!?!?)

Robert Smith (1791)

Jane Briggs (1796)

Margaret (1799)

Roger North (1797)

Samuel (1793)

James (with second wife) (1802/07)[7]

As an added bit of data, David Levi Todd (father of Levi) was born in Longford County Ireland, and moved to Pennsylvania, where Levi was born.[8]

The life of Levi Todd (son of David Levi Todd and purported father of “Lolly”), a significant pioneer, is also well-documented. Here are a few of the more relevant factoids: As mentioned above, he was born in 1756 in Lancaster or Montgomery County, Pennsylvania and raised in Louisa County, Virginia. He followed his brothers to Kentucky in the summer of 1775, and was stationed at St. Asaphs (now Stanford, KY) in 1779 when he married Jane Briggs. Levi served under George Rogers Clark in the American Revolution in the Illinois Country and went on to an illustrious (and well-documented) career in Kentucky politics, etc.

The Claim and the Conclusions

With the documentable facts and relationships established for both the Childs family and that of Mary Todd Lincoln, we can begin to draw some extremely solid conclusions. But first let’s review the claim:

The claim is that “Lolly” Childs, wife of Stephen Childs and grandmother to “Jennie” Ortt Elsheimer, was an aunt to Mary Todd Lincoln. This would logically make “Lolly” the sister of Robert Smith Todd and a daughter of Levi David Todd and Jane Briggs.

Now, with all due respect to cherished family folklore, let’s take a look at the Swiss-cheese-like holes in that theory:

First, and perhaps foremost, is the rather glaring fact that none of the well-documented children of Levi Todd and Jane Briggs happen to be named “Lolly.” Obviously Lolly is a nickname, but absent from the list of children is also any name that might possibly take Lolly as a nickname or pet name. In several genealogies consulted, “Lolly” is listed as “Sally”—a logical possibility, but no Sally exists among the children of Levi Todd either. Nor do we find a Polly, a Molly, a Laura, a Lillian or any other Christian name with a possible nickname link to “Lolly.”

Sidestepping this rather glaring issue with the claim for the moment, and assuming that one of the children of Levi Todd could have taken the nickname of “Lolly,” we find that all of Levi’s female children are well accounted for in their marriages and subsequent progeny by verifiable sources. None of these ladies ever married a Stephen Childs—in Vermont or anywhere else. Strike Two…..

For those who would still not be convinced by these rather large bits of evidence against the claim, there is the issue of geography. Levi Todd is well-documented as having moved to Kentucky around the year of “Lolly’s” birth (more specifically the summer of 1775). If Levi was in Kentucky, how was “Lolly” born in Connecticut? Added to this is the fact that there is absolutely no documentation for Levi (nor his parents) ever residing in Connecticut. Perhaps the listing of Connecticut on the 1850 census is not accurate, you say? This is a possibility, but in light of the other verifiable evidence submitted in “what we know to be true, part I” this would seem to be a remote possibility at best. Connecticut certainly rings true, given the other documentable information we have available, while not being from Connecticut poses more issues with what we know as facts. But “Aha!!” you say—Kentucky wasn’t a state in 1776, so perhaps the nomenclature is simply wrong. Not so—the area which became the State of Kentucky was previously claimed by Virginia, not Connecticut (though Connecticut did claim portions of Ohio….but northern Ohio, nowhere near Kentucky).

But to be fair, let’s say “Lolly” and Stephen lied about her birth location on the 1850 census (or that the poor benighted census taker got the information horribly wrong). This exposes a whole new set of problems with the claim. If we take the likely birth year of “Lolly” as 1776, then she would have been born about 3 years before Levi Todd was married to Jane Briggs (February 25, 1779) and four to five years before the documented birth of the eldest Todd child, Hannah, in 1780 or 1781. Before we dismiss the year 1776 as another “mistake,” let’s remember that this year is corroborated by 60 years of official U.S. Census information. “Lolly” is not only listed as being 74 years old in 1850, she also falls within the appropriate age brackets in the census returns for Stephen Childs from 1800 onward….and disappears in 1860, as she should if she died in 1854, which we know to be true. No—give or take a year—1776 is very probably correct.

The obvious argument to be made by those still supporting the claim at this point, in the face of the above-listed chronological realities, is that perhaps “Lolly” was mistakenly left off the well-documented lists of Levi Todd’s children—every time. Perhaps, they may say, this was because she was born before his marriage to Jane Briggs. A reasonably keen viewer of the list of Todd children in “what we know to be true, part II” will notice the highlighted possible birth year of one Ann Maria Todd—1778, one year before Levi’s marriage to Jane Briggs. Considering where Ann Maria appears in published lists of Levi Todd’s children, it is very possible that the date is a typo or mis-transcription, and should actually read “1788.” However, if the year 1778 is accurate, it demonstrates that Mr. Todd was capable of having children out of wedlock. So, if he had one, perhaps there was another. But if Ann Maria is routinely listed among his children, despite her being born prior to the marriage to Jane Briggs, then why wouldn’t a second pre-marital daughter also find her way onto a list somewhere—at least once?? It has been speculated that Ann Maria may, in fact, be our “Lolly.” If so, the year is still wrong and the ages don’t match up. Plus Ann Maria is documented frequently as being born in Kentucky, not Connecticut. Oh—and there’s also the annoying little fact that she died in the 1860s—in Indiana! (I have a photo of her tombstone.). So much for that theory. Ok, then ….perhaps “Lolly” was born to a mother other than Jane Briggs? Yeah…..maybe…..but not likely.

Adding to the chronological woes with this claim is the additional fact that, having been born in 1761, Jane Briggs (the wife of Levi Todd and most logical mother for “Lolly” under the claim) would only have been 15 or 16 years old in 1776—the year “Lolly” was born. Yes, women bore children at a younger age than we typically see today, but even in the late 18th century, a 15-year-old mother would have been unusual. So ok…..what about a 15-year-old unwed mother? Sure…..maybe…..but not likely.

So, to be “over-the-top” fair to those who would poke holes in all of this verifiable documentation, or produce counter arguments of “what if this or that information is incorrect?” I should point out that, indeed, there is a possibility (albeit very, very slight) that any of this information could be inaccurate to some degree. Nonetheless, the only “plausible” story (if it can be called that) we see emerging from all the documented evidence, that would still allow for the truth of the claim—assuming we still want to demonstrate the truth of the claim—is the following ridiculous speculation. If nothing else, it makes for entertaining reading:

One Levi Todd, somehow takes an undocumented trip from central Kentucky to some undisclosed location in Connecticut sometime probably in late 1775—perhaps just after he helped found Lexington, KY in June, 1775 (sarcasm, as well as emphasis, added)—and in the middle of the American Revolution, let’s not forget. And let’s not forget, too, that New York City and nearby Connecticut are on the front lines of that conflict for most of 1775/1776. However, undaunted by geography, enemy soldiers, and/or his civil and military calendar, Levi makes it to Connecticut, where he meets a woman lost to history and manages to get her pregnant. Running late for his next documentable date in history, he rushes back from Connecticut in time to be elected as a Gentleman Trustee at a town meeting in Lexington on March 29, 1776. (I am sure there are more documented “Levi sightings” in Kentucky between June ’75 and March ’76, but you get the point.) The return to Kentucky and his civic and military responsibilities bring young Levi to his senses, and he decides to keep forever secret his illicit foray into New England. Yet, in spite of his efforts to repress the incident and thus thwart future would-be genealogists, an aging woman in early 20th century Niagara Falls deciphers the truth, and thus the true lineage of the unhappy child born of this ill-advised northern jaunt appears in several small stories in a local newspaper. But instead of revealing the full facts of the child’s illicit heritage, the stories instead focus on her accidental (and illegitimate) relationship to the wife of the 16th President of the United States…

Given the verifiable facts of Levi Todd’s life, that’s about what would have had to happen to make the claim true. As fantastic as this story may seem, the alternative path to proving the claim to be true is perhaps even more fantastic. This second path would have to argue the following, despite significant evidence to the contrary:

-That the names of Levi Todd’s 11 children, though substantiated by numerous other

documents, are incorrect—or at least incomplete.

-That the birth year of “Lolly” as 1776, though demonstrated as plausible by other

documents, is incorrect, and perhaps falsified on a government document.

-That the birthplace of “Lolly” as Connecticut, though demonstrated as plausible by other

documents, is incorrect, and perhaps falsified on a government document.

-That the documentation for the marriage of Levi Todd to Jane Briggs, though

substantiated by numerous other documents, is likely incorrect, assuming “Lolly”

was born in wedlock.

For ALL of these statements to be false or somehow incorrect seems unlikely in the extreme. Certainly, historical “facts” can vary from source to source and are sometimes completely erroneous, but for such a string of otherwise-plausible or verifiable statements to be universally false seems to be really stretching things.

Perhaps the final and most damning argument of all against the claim having even a grain of truth to it is the fact that there is absolutely no known documentation, thus far, which states that the maiden name of one “Lolly” Childs was even Todd in the first place! Most, if not all genealogical records that list this woman at all, list her as either “Lolly,” “Lowly” “Loly” or “Sally” but never with a maiden name. The exceptions to this are the abovementioned newspaper articles and the Elsheimer family tree, but as mentioned earlier, there is no evidence to support these documents.

But wait!!!! The Genealogical Society of Utah possesses a roll of microfilm containing marriage records from Vermont during the years 1786-1858. As it is likely that Stephen Childs was married to “Lolly” in Vermont at some point prior to 1798, it seemed possible that a record of this marriage exists. Oakwood’s Michelle Kratts ordered a copy of the microfilm in order to investigate this tantalizing big of potential evidence. Alas, there was no record of the marriage of Stephen Childs, and thus no record of any maiden name attached to our poor Lolly.

Even taking as a given that “Lolly’s” maiden name was Todd, however, this in no way would prove that she was any relation to the wife of the 16th President, given the other glaring flaws in the documentation relative to the claim. As the saying goes, being born in a stable does not make one a horse.

As mentioned at the very beginning of this piece, it is often very difficult for historians to conclusively prove that anything is 100% true or false. Be that as it may, as of this writing there is not a shred of known verifiable documentation to support the claim that “Lolly,” Mrs. Stephen Childs, was the aunt of Mary Ann Todd, better known as Mary Todd Lincoln. By contrast, though there are still many gaps in the documentation that is known, there is an overwhelming amount of plausible, as well as verifiable, evidence that suggests Mrs. “Lolly” Childs was not related to Mary Todd Lincoln. In light of this overwhelming evidence, it is my considered opinion that the claim of relation to Mrs. Lincoln is but another piece of folklore that has failed to hold up to the test of historic scrutiny: If it looks like a duck, swims like a duck and quacks like a duck, it is probably a duck. But if it does NOT look, swim, nor quack like a duck, chances are it IS NOT a duck. Simply put, given the evidence available, there is no “linkin” Lolly and Mary Todd.

It should be duly noted, in case some readers would conclude that this exposition is simply out to criticize a cherished family story, that the author is a native of the great state of Illinois-- whose license plates still bear the motto: “Land of Lincoln,” and grew up in the shadow of Lincoln’s home, tomb, law offices and the capitol in which he delivered his “House Divided” speech. Thus the author would have liked nothing better than to be able to claim yet another connection between his home state and his adopted home of Western New York. Sadly, the evidence just didn’t turn up.

[1] Oakwood Cemetery burial register.

[2] All of this genealogical information is given on www.myoakwoodcemetery.com but is also substantiated in the Stephen Childs genealogy on www.werelate.org, www.ancestry.com and other locations.

[3] Stephen Childs genealogy on www.werelate.org. and other locations

[4] All census information taken from digitized original U.S. Census return documents, National Archives & Records Administration.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Thomas Marshall Green, Historic Families of Kentucky, 1889

[7] Daughters of the American Revolution Magazine, Vol. 59, No. 5 (May 1925), p. 313

[8] National First Ladies Library, www.firstladies.org.