By Michelle Ann Kratts

It was strange how we first met, for it isn’t everyday that a story walks into a library and then leaves for Arizona. Ironically, it was only moments before that I had typed Pete, my colleague, an email: We need an Armenian. We are forever working on our Oakwood Lives, stories of the residents of Oakwood…and, then, as if we had rubbed a genie’s lamp, an Armenian had appeared. Kathy, my coworker at the Lewiston Public Library, first noticed her. She had been helping her make some copies and when it was revealed that the copies were of an old family history interview—she came to me thinking that I may be interested. And so I was introduced to Nancy Gamboian—who certainly had many wonderful memories of her grandmother, Zozan. She told me some of Zozan’s story, briefly. Said she would only be in the area for a short time, visiting, gathering together some things that had belonged to her grandmother and then leaving again. I told her about our book and how we had been looking for a very special Armenian story. I asked if her grandmother happened to be buried in Oakwood Cemetery in Niagara Falls. She held onto her papers, her treasures, and all of the world’s energy converged on the place where we stood. I could feel doors opening and lights clicking on. She smiled. Yes, she is. It had never been so easy to find a story…even in the library. As if it knew it was meant to be printed and stamped and stacked within this sacred forest, made real and permanent by ink and a million reading eyes. Unfortunately, as is usually the case, things really don’t come so easy and the doors that had been opened flew shut and the lights went off. It seemed there was a problem. The story of Nancy’s grandmother was a secret and many family members wished to keep it tucked away with the cobwebs and the dust…in the land where the unpleasant things live on in oblivion.

It was strange how we first met, for it isn’t everyday that a story walks into a library and then leaves for Arizona. Ironically, it was only moments before that I had typed Pete, my colleague, an email: We need an Armenian. We are forever working on our Oakwood Lives, stories of the residents of Oakwood…and, then, as if we had rubbed a genie’s lamp, an Armenian had appeared. Kathy, my coworker at the Lewiston Public Library, first noticed her. She had been helping her make some copies and when it was revealed that the copies were of an old family history interview—she came to me thinking that I may be interested. And so I was introduced to Nancy Gamboian—who certainly had many wonderful memories of her grandmother, Zozan. She told me some of Zozan’s story, briefly. Said she would only be in the area for a short time, visiting, gathering together some things that had belonged to her grandmother and then leaving again. I told her about our book and how we had been looking for a very special Armenian story. I asked if her grandmother happened to be buried in Oakwood Cemetery in Niagara Falls. She held onto her papers, her treasures, and all of the world’s energy converged on the place where we stood. I could feel doors opening and lights clicking on. She smiled. Yes, she is. It had never been so easy to find a story…even in the library. As if it knew it was meant to be printed and stamped and stacked within this sacred forest, made real and permanent by ink and a million reading eyes. Unfortunately, as is usually the case, things really don’t come so easy and the doors that had been opened flew shut and the lights went off. It seemed there was a problem. The story of Nancy’s grandmother was a secret and many family members wished to keep it tucked away with the cobwebs and the dust…in the land where the unpleasant things live on in oblivion.

Nancy apologized. As much as she disagreed and felt that it was wrong to hide the past, that there are some stories that should be told in honor of those who have lived—there were those who loved her grandmother most deeply and it was still too soon and too much. They were not ready to give a part of Zozan away. So we did all that we could. We exchanged email addresses. She and Zozan were on a plane to Arizona and I was heartbroken. But as Pete and I were set on our Armenian story, we headed back to Oakwood, the place where Zozan sleeps, for inspiration.

I think my earliest memories of Oakwood are of the Armenians. They are the soldiers of Oakwood and their tombstones stand like sentinels to the passing cars. Husanian, Stepanian, Kartalian, Aloian, Sarkissian, Ghougasian, Kazarian….They greet you in the front, they cover the flanks, they hide under the trees and inside the bushes in guerilla fashion. They are tattooed with strange scripts and they tell you of places and wars that seem to have occurred somewhere over the edge of our history books. But even those who have little time for history can’t help but wonder…who were these Armenians?

Niagara Falls Gazette, April 12, 1959According to the Oakwood record books there are over 400 burials containing traditional Armenian names on the grounds. Most certainly, the number should be higher as many of the women married men of different nationalities and although they were of Armenian ancestry, their Armenian name does not appear in the cemetery records. In fact, my research has proven that there are many, many more full-blooded Armenians masked behind non-Armenian names. Who would ever know that Alyce Wilkinson was actually Alyce Der Arestakessian? She married Donald Wilkinson in Hamilton, Ontario, on October 4, 1947. Her own parents, Arshag and Eghees (Shamalian) had fled the Turks years before. And, perhaps, even more interesting is the story of Alyce’s daughter’s husband’s family. The Zelinsky’s who are also buried in Oakwood, had a secret of their own as their name wasn’t actually Zelinsky at all. Somewhere in Russia, following the forced migrations, their Armenian name was exchanged for a safer sounding Russian name and they moved that name across the ocean.

Niagara Falls Gazette, April 12, 1959According to the Oakwood record books there are over 400 burials containing traditional Armenian names on the grounds. Most certainly, the number should be higher as many of the women married men of different nationalities and although they were of Armenian ancestry, their Armenian name does not appear in the cemetery records. In fact, my research has proven that there are many, many more full-blooded Armenians masked behind non-Armenian names. Who would ever know that Alyce Wilkinson was actually Alyce Der Arestakessian? She married Donald Wilkinson in Hamilton, Ontario, on October 4, 1947. Her own parents, Arshag and Eghees (Shamalian) had fled the Turks years before. And, perhaps, even more interesting is the story of Alyce’s daughter’s husband’s family. The Zelinsky’s who are also buried in Oakwood, had a secret of their own as their name wasn’t actually Zelinsky at all. Somewhere in Russia, following the forced migrations, their Armenian name was exchanged for a safer sounding Russian name and they moved that name across the ocean.

But if a cemetery could tell a story—the Armenian story would begin in Oakwood’s back pocket where the crudest and earliest stones lie, toward the back right corner of the Town Ground. Here lie the Bedrasseans, Avakians, Gorpians, Hovievians, Kekorians. Here, also, lie heroes and heroines. The Hagopian tombstone tells a fantastic tale of a famous battle that gave Armenia its independence. Movses Hagopian is forever memorialized on his tombstone for fighting the Turks at Sardarabad. He actually left his new home in the United States to return to Armenia and fight for his homeland. Luckily, he made it back here, alive. But as glorious as his life had been, his wife’s epitaph is even more intriguing for she is memorialized as an “unusual mother, philanthropist, business woman, civic leader who taught the love of family, ethnic pride, generosity, arts and fellow man…” As we pass by and move onto others, the Hagopians don’t hesitate to add one more commentary and it sums up the story of so many of their lives…War is the failure of civilization and a reversion to hate which is our cruelest base emotion…

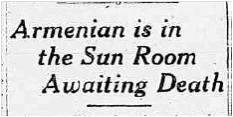

The Sun Room was in the city’s quarantine hospital Niagara Falls Gazette, May 14, 1915 Although there are great triumphs here there are also great tragedies. Alikison Kekorian—who may be the very first Armenian buried in Oakwood, back in January of 1913—had been on his way to work when he was killed by a Le High Valley passenger train in Niagara Falls. He was killed instantly. His head cut off. Armenag Ohanesian was only twenty-four when he found himself awaiting death in the sun room of the city quarantine hospital. He had been turned out of an Armenian boarding house on the corner of Erie and Buffalo Avenue with only the very few items he called his own and an old mattress. Finally after a friend alerted a nurse, Miss Josephine Eddy, and the city health officer, Dr. E. E. Gillick, it was revealed that he was in the end stages of tuberculosis and he was taken to the quarantine hospital where he was “excellently fed and cared for by keeper Walton and his wife…”

The Sun Room was in the city’s quarantine hospital Niagara Falls Gazette, May 14, 1915 Although there are great triumphs here there are also great tragedies. Alikison Kekorian—who may be the very first Armenian buried in Oakwood, back in January of 1913—had been on his way to work when he was killed by a Le High Valley passenger train in Niagara Falls. He was killed instantly. His head cut off. Armenag Ohanesian was only twenty-four when he found himself awaiting death in the sun room of the city quarantine hospital. He had been turned out of an Armenian boarding house on the corner of Erie and Buffalo Avenue with only the very few items he called his own and an old mattress. Finally after a friend alerted a nurse, Miss Josephine Eddy, and the city health officer, Dr. E. E. Gillick, it was revealed that he was in the end stages of tuberculosis and he was taken to the quarantine hospital where he was “excellently fed and cared for by keeper Walton and his wife…”

Niagara Falls Gazette, January 14, 1916 The Mooradian family was one of the earliest and most prominent Armenian families in Niagara Falls. A rug company still bears the family name. It is believed that John and Altoon Mooradian came to Niagara Falls around 1906. The original Mooradians operated a restaurant on 1oth Street and young Alice became the youngest graduate of Niagara Falls High School and a great leader in the community until her death on November 23, 1992. In fact, just recently I found Pete lingering around Alice’s grave—pretty much in the middle of the cemetery-- with a pair of hedge clippers. This fabulous woman, now lost to time, had disappeared behind the arms of a giant and overgrown bush. But not for long, as Pete spent the afternoon gallantly rectifying the situation.

Niagara Falls Gazette, January 14, 1916 The Mooradian family was one of the earliest and most prominent Armenian families in Niagara Falls. A rug company still bears the family name. It is believed that John and Altoon Mooradian came to Niagara Falls around 1906. The original Mooradians operated a restaurant on 1oth Street and young Alice became the youngest graduate of Niagara Falls High School and a great leader in the community until her death on November 23, 1992. In fact, just recently I found Pete lingering around Alice’s grave—pretty much in the middle of the cemetery-- with a pair of hedge clippers. This fabulous woman, now lost to time, had disappeared behind the arms of a giant and overgrown bush. But not for long, as Pete spent the afternoon gallantly rectifying the situation.

Then there were the Sarkissians. Satenig Sarkissian was born into a noble lineage in Caesaria, Turkey, in 1883—the Matosian Der Stepanian family--that could boast historical, political and religious leadership in Caesaria for over three centuries. Her family came to Niagara Falls around 1916 and was active in Armenian causes. Her rug weaving had been on display at the New York World’s Fair. The Jamgochians were also an important family in the history of the Armenians in Niagara Falls. Arosloog came to Niagara Falls around 1920 and was a teacher of the Armenian language for children. In 1935 she had a graduating class of 55 pupils.

The Armenians began pouring into Niagara Falls during the late 1890’s and early 1900’s. Mostly refugees from unspeakable horrors, they worked in the chemical factories and lived on the East Side, residents of what was known as Tunnel Town. Some, like Sahag Aboian, operated businesses such as the aptly named, Liberty Restaurant, on the corner of Erie Avenue and Tenth Street. Ninth, Tenth and Eleventh Streets contained the greatest Armenian populations. They came as a result of the policies of Abdul Hamid II, leader of the Ottoman Empire. Abdul Hamid believed the woes of his empire stemmed from the endless persecutions of the Christian world. The Ottoman Armenians, who happened to be Christians, represented a sort of extension of western hostility and they lived in the very heart of their empire. So to prevent persecution and misery, he decided the wisest move would be to engage in a national policy of persecution and misery. True numbers will never be known, however experts estimate that between 80-300,000 Armenians were systematically killed between the years of 1894-1896 and about 50,000 children were orphaned. Again in 1909, the Adana Massacre resulted in more anti-Armenian pogroms and the death of close to 30,000 Armenian men, women and children.

Lady Anne Azgapetian, the widow of General Azgapetian, spoke at the Hotel Niagara in 1929 for the Near East Relief. Courtesy Library of Congress The greatest tragedy to befall the Armenian people was yet to come, though, and brought about the mass migrations to the United States and a movement, very active in Niagara Falls, called the Near East Relief. The Near East Relief, originally known as the American Committee for Syrian and Armenian Relief, was founded in 1915 in response to the massive humanitarian crisis that resulted from the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire--for the period from 1915-1917 utterly devastated the Armenian population. Americans active with the Near East Relief felt that they “bore a special burden to rescue the Armenians” as they were Christians from the Holy Land. Huge advertisements filled the American newspapers and told a romanticized tale of the horrific conditions faced by the Armenian people. Through public rallies, church collections, and charitable donations, millions of dollars were raised and delivered to the American embassy in Constantinople where missionaries would go deep into the ravaged country and distribute any aid. Perhaps my own interest in the Armenian story can be linked to this singular and particularly brave woman, Ms. Mary Margaret Wright, who had left her comfortable home in sleepy Lewiston, New York, to administer aid in Turkey. On January 25, 1919, the Department of State, Washington, D.C., received a letter from the American Committee for Syrian and Armenian Relief, which stated that they would be “sending a relief commission to Turkey to assist in carrying on relief work among the war sufferers in that country…Miss Mary Margaret Wright…Lewiston, NY, is one of this group and in view of the work in which she is to be engaged, the Committee earnestly requests that every possibly facility be afforded her in securing the necessary passport for the journey…the party plans to go direct from NY to Turkey on a transport furnished by the United States government…”Ms. Wright just happens to be, in a way, my own progenitor, for, as well as a writer, she was the very first librarian at the Lewiston Public Library and how strange that circumstances would come full circle, just around 100 years later, and a librarian from the Lewiston Public Library would find herself entangled in the story of the Armenians, yet again…

Lady Anne Azgapetian, the widow of General Azgapetian, spoke at the Hotel Niagara in 1929 for the Near East Relief. Courtesy Library of Congress The greatest tragedy to befall the Armenian people was yet to come, though, and brought about the mass migrations to the United States and a movement, very active in Niagara Falls, called the Near East Relief. The Near East Relief, originally known as the American Committee for Syrian and Armenian Relief, was founded in 1915 in response to the massive humanitarian crisis that resulted from the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire--for the period from 1915-1917 utterly devastated the Armenian population. Americans active with the Near East Relief felt that they “bore a special burden to rescue the Armenians” as they were Christians from the Holy Land. Huge advertisements filled the American newspapers and told a romanticized tale of the horrific conditions faced by the Armenian people. Through public rallies, church collections, and charitable donations, millions of dollars were raised and delivered to the American embassy in Constantinople where missionaries would go deep into the ravaged country and distribute any aid. Perhaps my own interest in the Armenian story can be linked to this singular and particularly brave woman, Ms. Mary Margaret Wright, who had left her comfortable home in sleepy Lewiston, New York, to administer aid in Turkey. On January 25, 1919, the Department of State, Washington, D.C., received a letter from the American Committee for Syrian and Armenian Relief, which stated that they would be “sending a relief commission to Turkey to assist in carrying on relief work among the war sufferers in that country…Miss Mary Margaret Wright…Lewiston, NY, is one of this group and in view of the work in which she is to be engaged, the Committee earnestly requests that every possibly facility be afforded her in securing the necessary passport for the journey…the party plans to go direct from NY to Turkey on a transport furnished by the United States government…”Ms. Wright just happens to be, in a way, my own progenitor, for, as well as a writer, she was the very first librarian at the Lewiston Public Library and how strange that circumstances would come full circle, just around 100 years later, and a librarian from the Lewiston Public Library would find herself entangled in the story of the Armenians, yet again…

I must admit that my encounter with Zozan, with the Armenians, started with a lie. As a genealogist, obituaries are usually the key for my research, but Zozan’s taught me that they can be carefully constructed to hide the truth. Her obituary states that she had been born on January 30, 1910, the daughter of Ohannas and Sarah Sahagian. In reality, she was not sure when she was born and that kind couple called the Sahagians were not her parents, at all. I spoke with her daughter in law and I told her that I would even be willing to tell Zozan’s story without any names, if that would make it easier. Perhaps their reluctance to give us the details of her name could impart the harsh reality of the situation more than anything I could ever write. It was very obvious that this story, the story of Zozan’s life, was not over yet.

And then it happened. After many, many months, Nancy was in Lewiston again and this time she said yes. The time was right. She told me about the Armenian Genocide Museum of American—located just two blocks from the White House in Washington, D.C., slated to open sometime soon. She had passed her grandmother’s story and photos onto the Museum and she was finally ready to share it with us and the people of the city that gave Zozan a home, Niagara Falls. Nancy promised to email the file to me as soon as she made it back to Arizona.

Unfortunately, a crazed gunman from Tucson held things up even more. Nancy had returned to Tucson just hours before over 20 people would be shot at a Safeway Grocery Store—including a United States Congresswoman. The nation paused and the residents of Tucson had their lives disrupted for a bit. It seems that some things never change and violence continues to put a hold on things where Zozan is concerned.

And so when the story finally came, it was during a snow storm and I was very, very sick. I opened it on my phone and so much of it filled my head with nightmares. I couldn’t believe what I had gotten myself into. It was horrifying. What could I do with this? How can words alone bring peace to this family? I had to put it down and a day later, as I was sitting in a room at Immediate Care, burning with a fever and bronchitis, so still the light sensor believed it was alone and clicked off…it all came to me. A man and a woman chattered outside my door about a wedding and somewhere in the waiting room the complimentary water cooler bubbled and burped. Little by little this world of mine slipped away and it was here, in this doctor’s office, with my eyes shut, that young Zozan made her appearance to me. More bird than woman, she simply walked off the train—a certain rhythm of flight in her steps. She said goodbye to the nurse who had stayed with her through the journey and the train left. She had nothing but the dress she wore, a black fur collared coat, and the shoes on her feet. She had thrown her suitcase into the water a long time before. Its contents had become rotten.

In this half-delirious state, somewhere between things of this world and things of another, I was ready to listen and to see. And I saw, first, that in the beginning, there was a crime. A crime willingly committed many years ago had precipitated all of the events leading up to that final moment when a young girl walked off a train and into a city on the other side of the world. In the beginning, a man called Markar Atamian simply would not leave his land. Every measure had been taken to warn him that he could not have this land anymore and yet this man stood straighter and taller and his eyes grew deeper and fierce. It was his land and he loved his land. Perhaps it wasn’t so much a matter of the fields and the mountains that unfurled like a flag behind his house. Or the wheat and the beans, the peaches, plums, apples, the pear trees, the soil so rich and beautiful because of the cows, the bread that baked in the deep pit dug into the floor of the house, the tonir. It was all a magical formula and Markar Atamian knew that his ancestors had worked on it for centuries to make it perfect. And it was paradise. For Erorin (Eroretzis)—a Herehan village east of Lake Van at the eastern border of Armenia--was no ordinary parcel of land. Armenia lies in the highlands surrounding the biblical mountains of Ararat—upon which Noah’s Ark is said to have come to rest. This area is sacred to many world religions—a beginning point. In fact, one incredible questions remains to this day: was this the location of the Garden of Eden?

A view from Lake Van (now Turkey) Courtesy Cornell University

A view from Lake Van (now Turkey) Courtesy Cornell University

But it was more than the land—the physical boundaries, the parcels, hectares and miles, the buildings stacked together by men. It was the molecules of oxygen that entered their airways, the way the mountains took in their breath and sent it back out. It was the bread that four women kneaded and baked. It was the mule that brought a bride to her husband. Everything was a perfect puzzle piece that fit just right. There was a deep pride in knowing you belonged in one place and one place alone. The land provided the clay that fashioned its children. The land was the mother and the father. The grandparents and the children. The past, the present and the future.

So…when taken into context, it is not so hard to understand why Markar Atamian had great difficulty handing over the land of his fathers, even as he knew that by decree issued on April 24, 1915…

The men shall be taken first….

The men had plans. They had heard what was happening in other parts. They took the men first so the women and children would have no one to protect them. So they made their plans. They hid guns, prepared hideaways within the depths of the caves that dotted the mountainside. Their armor was their land and she held them and protected them as long as she could.

And it happened that one day came as any other. The sun rose in the sky but the men knew it was time to go to the caves. There was hardly any time at all to bring any food or water, but they still went. Word had come that the Turks were on their way to cleanse the village of men. So they went and they waited.

But it wasn’t an ordinary day at all. Little Zozan, Markar’s sweet daughter, was playing outside when they came. There was much shouting and banging. Her grandfather, whom she lived with, had known some of the angry men for they had drunk wine together. But that did not stop their dismal business. They came into the house with their horses and they beat her grandfather and her grandmother to a pulp and then put their lifeless bodies into the bread oven, the tonir.

When night fell and soft crying could be heard throughout Hereran village, when the great killings had subsided for the moment, the men came down from the mountains and beheld the most horrific sight. The angry ones knew the men would come back, that they would not be able to stay away for long and the Turks followed them back into the hills. They found 25-30 men and beat and killed them, as well. Zozan overheard this from a woman who was dressed as a Turk.

There was a time of grieving. Then some quiet and the little girl came out to play, again—as a little girl must. But the men returned with their horses, and they broke down the doors. It was on this day that they killed the children. Two of her uncle Armenag’s children. Gone. The men had been away in the caves. Waiting. It was the end of all things she had ever known to be true. Her mother, Iskoui, had buried a trunk full of all of their family treasures within the dirt floor—but they were found by the Turks when they jammed their sticks and guns into every single space. There was nothing left.

The women and the children were taken and herded into the place set aside for darkness; a nearby home with four corners and a roof over human darkness. The beautiful ones were chosen and sent off to keep pleasure for the Turks. They would never be seen again. Here, the walls and the ceilings and the floors buckled and cried out with a chorus of voices when the blood of a mother and her child fell to the ground. They had slit open her stomach, twirled the new child on the end of a sword. How can I forget? How can I forget? How can I forget? a little girl asked herself. She knew that she would never forget. This was a piece of luggage—heavy and burdensome, rotten—that she would carry for many miles.

Ankeen, who spoke Turkish, helped them to escape and they found temporary peace when they hid in the side of a mountain. But there were other Evils who went by the names of Hunger and Thirst and they followed the children into the mountain. The little ones cried for water most of all and their sadness travelled until it reached the place where the men had waited. One man became mad from the crying and left the cave to fetch water for the babies and some of the women also left for water. But they were all fooled and they were taken out of hiding one by one. All of the men were killed and the women who were not killed were brought to another house. This time the survivors were given one half of a fish and a small piece of bread. It was here that they were told that it was time for them to leave for the Armenian District, an area set aside by the Turkish government for the displaced Armenians. On September 13, 1915, the Ottoman parliament had passed the Tehcir Law, or the Temporary Law of Expropriation and Confiscation. The Death Marches began and Zozan took one last look at this place her ancestors had made their home for an eternity. She would never see this place again, and her childhood—beaten and lifeless—fell somewhere into a crack between a cooking pot and the glistening edge of a sword.

And so they walked and they walked and they walked. They were beaten when they stopped. Little by little their numbers were diminishing. The babies died because they had no food and no water. Her cousin carried her dead baby for many days. For what does one do with a dead baby when there is all this walking? You bury them in the air.

There was much craziness, too. This new world was a strange horror. Boys were dressed like girls or hidden under their mother’s skirts. If the Turks saw a boy they slit his throat.

I remember a beautiful boy, about fifteen years old, with blue eyes…they cut off his head…he teetered headless and then fell…we screamed…we screamed… I will never forget….

Enter. A cold dark church. Imagine it to be the closing scene for the mothers and the children. The light is soft and breaking through an opened window. Iskoui huddles her little daughters into her body, giving them whatever softness and motherwarmth she has left. Zozan and little Siranoush listen as the world closes away. Only words and prayers to fill the empty dark spaces. And terrible Hunger. But as Iskoui sees the curtain coming down upon her life a certain sense of fearlessness covers her and fills her. She flashes her eyes at the Hunger and tells the little girls that it would be better to die than to take any bread from a Turk….

The next day the curtain did come down on Iskoui. She knew when the sun came up that each breath was a countdown. Each step was closer to gravesend. Even as the women and the children cried and screamed to no avail—they marched on. Starving, still so thirsty. At the Turkish village they stopped and some women who were browning wheat gave them each a half a cup. It was much like heresah—but little or no water. Precious water. Their thoughts were drowning in rivers of water. Maybe their walk would end at the sea. Cool, blue…endless. A mirror like the sky. They walked until they could hardly feel their legs. And they carried their babies, sticky and wet, screaming, as far as they were told. And still at every stop, the most beautiful ones were separated and taken into slavery.

They came to a field where Turkish women were busy threshing wheat. But it was all a ruse. The women disappeared and shooting began from somewhere in the mountains. Between thirty and forty women and children were massacred here. In this field of wheat. The women, who had been threshing the wheat, returned with clubs and they beat any who were not yet dead. Even the babies. Then they searched the bodies for valuables.

Zozan watched as her mother fell. Just a little girl, she did as a little girl must, and she clung to her mother’s dead body. She held on and felt as the last of her warmth moved into the earth. It was safe below the earth and far away from the madness that carried on above with the grass and the trees and the living. She laid there with the piles of bodies and then even Saranoush was murdered and thrown upon the pile.

Her bloody hair covered my body…

She stayed there for a time. In the wheat field. A strange stillness fell upon the landscape. In this scene the paint was not dry yet and it dripped from little Saranoush’s mortal wounds and covered everything she ever was.

Finally, some Armenians came and gathered those few who happened to be alive and took them to a small home near a grape vineyard, where the men would often hide. Here Zozan came upon her father…who ran around like a mad fool when he saw his daughter covered in dried blood. He threw a blanket over her as there was no water to clean her. It was far too dangerous to go out to the well. The blood dried into a second skin. And then Markar—and the men-- had to leave again. Back into the mountains. The women and the children were told to stay and wait. Again. This would be the last time, Markar and Zozan, the father and his daughter, would ever lay eyes upon the other…except in the land of their dreams.

The marching soon continued though all the women and the children were so tired and so broken. They could not help but envy the birds with their wings. How lucky to be able to lift away from the men who would hit you on the head with their rifles and leave you to die in a river! To rise in flight, in curls of smoke. They dreamed of escape.

Zozan said it had to have been April or May because she remembered the green grass and how they tried to eat the green grass. They were so hungry. They imagined the rain soaking into the blades, filling little healthful thimbles of water. But the Turks even cast them away from the grass. They never allowed them to stop long enough. And those who did stop for too long were killed and their bodies left along the way. All they were given to eat was a few handfuls of fried grain. Enough to keep them alive and to keep their legs walking. But never enough for anything else.

Zozan was completely alone now. Except for the kindness of a cousin, she had no one to watch out for her. No mother left to give away her strength. She had only the picture in her mind of a mother, now gone. It was a picture she liked to keep framed in a sort of warm halo of light and peace. An image from a long time ago before the men and their horses broke into their house. But she also loved the Iskoui who held onto her and Saranoush so fiercely in the old church.

Eventually the small group—there were only twenty five left—came to a bridge. They were so far from home. They were told that this was the end, that they must walk across this bridge and on the other side there would be Armenians who would take them in. But they were so afraid. What would really be at the other side of the bridge? There had been so many tricks along the way. The survivors did as they were told, they were too weak to do otherwise, and it turned out that there were Armenians who took them to a house and gave them little cans of meat and raisins. Zozan’s cousin, Nano, warned her not to eat too much, though, as her stomach would not take such heavy food so soon.

For a time this group of homeless people lived in an open field. There was a wall that separated them from a field of potatoes and cabbage and sometimes in the night they would steal whatever they could and cook over a fire. A miserable rain came down for three days straight. Their only shelter was one tree and it opened up its arms and took in everyone that could fit.

Finally the sun came out and dried everything….

An Armenian man came one day and asked if he could take Zozan to live with him and his daughter. He had probably lost much of his family, as well. Nano encouraged her to go with this family and she did. For a few months she pretended she was someone else. That she had never been Zozan Atamian. She had never seen the house in Erorin. Nor the people. When they filled the landscape of her dreams she imagined they were just faces and places she had somehow come across one time or another. She played with the daughter and watched as they made piles of thin bread, called lavash. But the shouting and the shooting and the fighting picked up once again and the Turks were back. The family who had taken her in told her that they would be leaving and that she must find her way herself. She cried and she didn’t know what to do. She followed behind the family for awhile and tried to keep up with them—though they tried just as hard to lose her in the crowds. She was lost. She found herself in a field where a man picked up this lost and miserable little thing, no longer a little girl. He gave her food and most importantly she met up with Nano once again. Then the man who had found her took her to an Armenian orphanage. Before she left, Nano’s wife made her a dress out of potato sacks.

The orphanage was in Leninakan, Russia, and it was not immune to random and brutal attacks by the Turks, for at night they would break through the doors and steal the beautiful girls. The Armenian woman in charge could only stand back and watch as they took what they wanted. It was here where cots lined the cold spaces. Where the children who broke the rules were beaten, almost to death. Zozan recalled the menu, even years later…

Breakfast, we ate bread dipped in syrup

For lunch, a piece of bread

At night, some cabbage soup, if available

Luckily, the dreaded Leninaken was not a permanent residence. Strangely, a young man on the other side of the world, Zozan’s uncle, who had made it to America, to Niagara Falls, had heard of her plight and sent his sister money and orders to retrieve Zozan from the orphanage. His goal became to find a way to get Zozan to America. It took a very long time as there were rules and laws involved with immigration. No matter how he looked at it, only immediate family members were allowed to immigrate. The fact became apparent: according to the law, Zozan would never be able to come. It took Harry Atamian close to five years, but in that time he conceived of an ingenious illegal operation that would bring a young girl out of an inexplicable nightmare and into a new world of freedom. He offered his friend, Ohannes Sahagian, $200 to be a part of the scheme. He would make believe Zozan was his own daughter, Aghavni, who had actually died in Armenia. In the end it worked. Zozan buried herself deep inside those quiet spaces and with a miracle brought another girl back to life.

Zozan Gamboian and Harry Atamian. Courtesy Nancy Gamboian On August 23, 1929, a letter was posted to Mr. Ohannes Sahagian, of 126 12th Street, Niagara Falls, New York, from General Agent, Staley F. LaVey.

Zozan Gamboian and Harry Atamian. Courtesy Nancy Gamboian On August 23, 1929, a letter was posted to Mr. Ohannes Sahagian, of 126 12th Street, Niagara Falls, New York, from General Agent, Staley F. LaVey.

Dear Sir: We have just been advised by our Moscow office that Miss Zozan Sahagian will probably receive her Russian passport at the beginning of next month. As soon as she is in possession of same, she will be sent to Riga. Further information from abroad will be transmitted to you without delay. Yours very truly….

Before Zozan left, her aunt bought her a heavy black coat. A neighbor made her a dress, for she hadn’t even had one. She stayed at a hotel for one week where she waited with strangers for the ship to take all of them to America. And then she boarded the ship. She was given a small room on the second floor. She had the top bunk and an old woman slept on the bottom. The boat left and she felt herself drift helplessly into the emptiness that lived between two worlds. Seasickness enveloped every inch of her body. She refused to eat anything at all. She thought her life was over and that she was near death. Finally four people held her down and forced her to swallow some pills. Sweating and kicking and crying, she fought them with all of her might. In the end, out of sea water and endless sky, with her feet scratching against the wood of the tossing ship, a new girl was born. And the first thing she did was rid herself of her luggage. There were things she didn’t want to carry anymore. The stinking things.

There was a smell from my suitcase so I threw my suitcase and the food, cheese, garlic, and bread into the sea….

Throughout the journey she hadn’t spoken to anyone at all, nor eaten anything but a few black grapes. Now an Armenian woman brought her tea and crackers and she ate and she spoke. Soon she was in the new world. New York.

I saw the beautiful Statue of Liberty.

She was surprised to find a bit of home here at Ellis Island, in this new world. There were kind Armenian faces, voices, all around her. An Armenian man looked over her papers. Through the crowded room she saw there were nurses taking care of the sick and elderly while paperwork was being furiously processed. Zozan was so ill that a nurse stayed on the train with her all the way to Niagara Falls. On the trip her eye had been swollen with infection and then subsided just in time for the train to pull into the station at 3rd and Falls St. She moved down the steps. Weak, frightened. Incredulous. She said goodbye to the nurse and the nurse left on the train. She was here. Finally here at this new chapter of her life. This place, where the trains disembarked thousands of people to a new chapter, new life, is long gone. There are only ghosts now who greet you at the corner of 3rd and Falls St. Many, many ghosts.

Zozan hugged and kissed her uncle. It was really him! But, Mr. Sahagian, her “father,” she shook his hand.

She lived with the Sahagian family on lower 12th Street for six weeks. Food was plentiful. Uncle Harry spoiled her. He would give Mr. Sahagian money for her keep. And Mr. Sahagian would make eggs with tomatoes. It was not paradise, though. There was always loneliness and emptiness.

It was 1930. I was twenty years old when I came to this country. I couldn’t work. I did not know the language. I had no one.

When the six weeks were up, on May 18, 1930, Zozan was married to Arshag Gamboian. Arshag was much older than her. He had come from her old village in Armenia and had lost his wife and children to the Turks. He was the sole survivor of a large family. He had taken part in the battles of Erorin and Lim where, along with the combined forces of Ovan, they were able to liberate 12,000 people. Arshag was very jealous. She had no choice but to marry him. Her bridal attire was a hodge podge of borrowed articles…the dress, from Alice Hatchigian…the veil, which desperately needed to be cut down, from Mamie, an Italian woman. After a beautiful wedding at St. Peter’s Church a reception was held in a big and long room upstairs at the Old Veteran’s Hall on East Falls and 12th Street. There was a lot of food—Arshag insisted—even things such as oranges from Mr. Toorigian’s grocery store—though Michael Aloian insisted oranges were not suitable for a wedding.

Zozan and Arshag Gamboian, circa 1930. Courtesy Nancy Gamboian The Gamboians lived on the East Side all of their life. Arshag worked for the Aluminum Company of America and the city water department. Zozan gave birth to six children: Varantat (David), Lolizar/Lalazar (Lollie), Durtat/Drtad (Samuel, Smile), Mary, Anaheet/Anahid (Margie), and Michael.

Zozan and Arshag Gamboian, circa 1930. Courtesy Nancy Gamboian The Gamboians lived on the East Side all of their life. Arshag worked for the Aluminum Company of America and the city water department. Zozan gave birth to six children: Varantat (David), Lolizar/Lalazar (Lollie), Durtat/Drtad (Samuel, Smile), Mary, Anaheet/Anahid (Margie), and Michael.

Little Mary Gamboian died as a result of her burns. Courtesy Nancy Gamboian In November of 1938, tragedy fell upon Zozan once again when her beloved little girl, Mary, just four years old, fell into a bonfire near Buffalo Avenue and 12th Street. She had been playing near the fire, roasting potatoes on a stick when her dress caught fire. An unidentified youth tried to save her but it was too late. A neighbor had just come home with a huge barrel of cooking oil and he pierced it and smothered her in the oil---hoping to save her, as well. Instead, it prevented her body from cooling. She was burned from her ankles to the top of her head. After being rushed to the hospital Dr. John V. Hogan worked over her for hours but he could not save her. Little Mary Gamboian is buried in Oakwood Cemetery, toward the front of the Town Ground area. Pete and I like to stop by her sad little grave. I imagine Zozan spent much time at this corner of earth and stone.

Little Mary Gamboian died as a result of her burns. Courtesy Nancy Gamboian In November of 1938, tragedy fell upon Zozan once again when her beloved little girl, Mary, just four years old, fell into a bonfire near Buffalo Avenue and 12th Street. She had been playing near the fire, roasting potatoes on a stick when her dress caught fire. An unidentified youth tried to save her but it was too late. A neighbor had just come home with a huge barrel of cooking oil and he pierced it and smothered her in the oil---hoping to save her, as well. Instead, it prevented her body from cooling. She was burned from her ankles to the top of her head. After being rushed to the hospital Dr. John V. Hogan worked over her for hours but he could not save her. Little Mary Gamboian is buried in Oakwood Cemetery, toward the front of the Town Ground area. Pete and I like to stop by her sad little grave. I imagine Zozan spent much time at this corner of earth and stone.

Zozan lived in Niagara Falls most of her life. She missed the orchards back in Armenia most of all and she transferred her love for her homeland to her own garden. A special garden of Eden fashioned by the work of her hands, fresh water, new earth. But the same sun. Many of the immigrants to Niagara found much pleasure in their special gardens. My great grandfather, Francesco Fortuna, was said to have smuggled special seeds in the rim of his hat when he entered the United States. My lingering memories of him carry me back to his gardens, as well. And, most of the back yards downtown have the remnants of grapevines, little skeletons, crawling up a paint-chipped trellis. Little bridges to other worlds…

Zozan’s granddaughter, Nancy, was always curious about her grandmother’s other world. She would ask about Armenia and Zozan would hush her.

Oh, Nancy, it’s too sad. I can’t….

But there were some stories and memories that inevitably fell from her lips. And on December 8, 1988, Nancy’s mother, Shirley Markarian Gamboian, found her in a story-telling mood. For some reason, she talked and she talked. Shirley pulled out a tape recorder. In her native tongue, Zozan lost herself and Shirley went on a trip back in time. She kept the tape, cherished the tape, and translated the words into English. In 2011, these words, this story, were reborn once again. An international lawyer, who flies between the US and Yerevan, packed them in her suitcase and hand delivered them to the Genocide Museum in Yerevan, Armenia. It was an emotional moment for the family.

A piece of her is finally back home!

Arshag died on December 18, 1961. Zozan died on April 1, 1999. April Fool’s Day had always been her favorite holiday and her family likes to think she had the last laugh. It was believed that she was about ninety years old. Did she even know, herself?

I don’t know if Zozan’s story will ever come to an end. There will always be mysteries surrounding her life. I tried to discover the true meaning of her interesting and unique name, Zozan. It does not appear in Shirak’s Dictionary of Armenian names. Nancy remarked that her friend, the international lawyer, believes that it is derived from “Susan.” Susan, or Shoshan, is an ancient and sacred name in Hebrew scripture meaning lily or rose. The verdict is not out as to which flower it may be, but I believe that in Zozan’s case, a rose by any other name would smell as sweet.

Flowers for Zozan

Flowers for Zozan